Old C64 disks might just surprise you by still being readable. But the clock is ticking, so how can you save your old disks? And, is it okay to do so — or do you risk prosecution…?

Is archiving Commodore 64 disks legal?

If you’re digging old data off vintage media, you’ve probably already wondered where the law stands. Archiving disks is harmless, right? After all, you’re just making a backup, but be aware that copyright rules vary wildly depending on where you live.

So what can you safely archive?

If the disks contain your own data, you’re on solid ground. Save games, artwork, word processing files, spreadsheets, BASIC programs you wrote yourself — all of that belongs to you. If you still have the physical disks, you can copy them to modern formats such as .d64 images without losing sleep over it.

Public domain software is also fair game. Long before “open source” became a thing, PD software circulated via bulletin boards, magazine cover disks, and mail-order libraries. The key point is that its creators deliberately gave up ownership. If you still have PD disks — or typed in programs from magazines and saved them to disk — you’re free to archive those too.

Those type-ins matter more than you might expect. If you owned magazines or books with pages of code to type into your Commodore 64, and you saved the results to disk, those disks are part of your personal computing history. Archiving them is entirely reasonable.

Why bother archiving old disks at all?

Let’s be honest: if all you want is to play Impossible Mission again, the internet has you covered. Disk images are everywhere, even if their legal status is… questionable.

But this isn’t about rebuilding a pirate library.

Your own disks are different. They’re snapshots of how you actually used your C64 — half-finished games, crude pixel art, save files, experiments that went nowhere. In my case, I found backups made with fastloaders, SEUCK projects I never quite finished, and artwork I’d completely forgotten about.

That kind of material doesn’t exist anywhere else. Once a 5.25” disk dies, it’s gone for good.

Do 40-year-old disks even still work?

Sometimes. Often surprisingly well — but it’s a gamble.

5.25” floppy disks are vulnerable to all sorts of problems: magnetic degradation, dust, fingerprints, warped sleeves. Storage matters. A sealed box in a cupboard is far better than a shoebox in a loft.

Before inserting any disk, give it a visual check. Bent disks are risky, and dirt inside the sleeve can scratch both the disk and the drive’s read head. If you hear repeated clicking when loading, stop. That can indicate head alignment issues or a damaged disk.

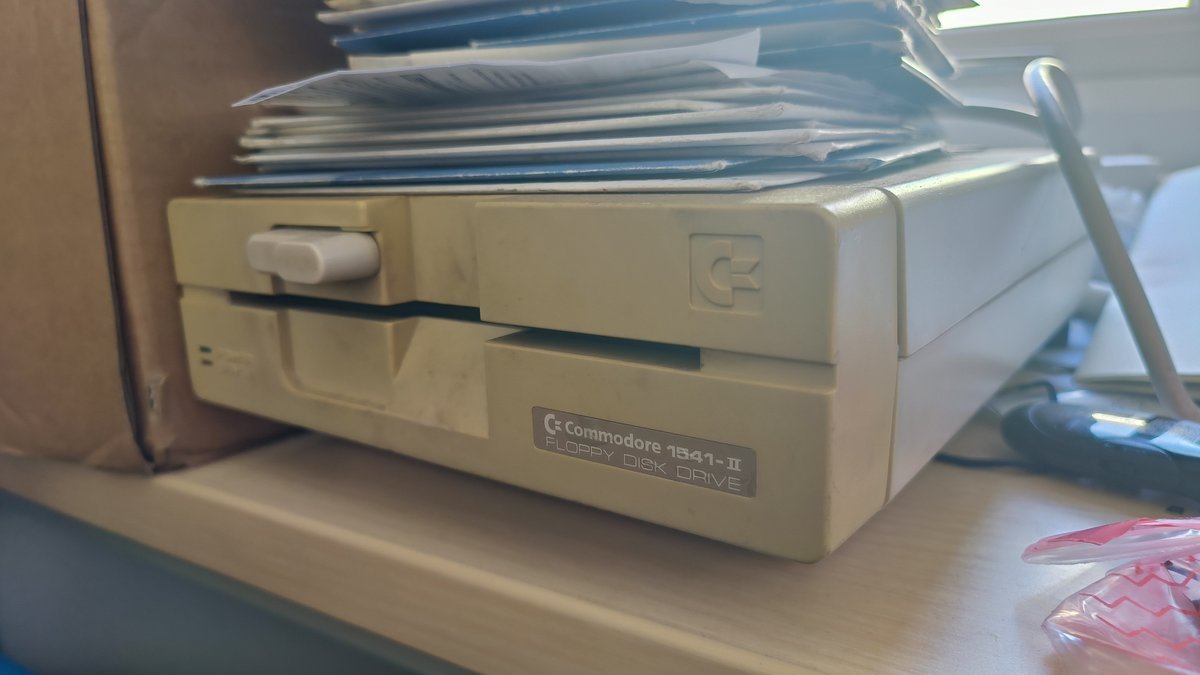

Checking a Commodore disk drive

The same goes for disk drives. A Commodore 1541 or 1541-II can be repaired, but replacement parts aren’t cheap, and repairing is invariably time-consuming.

Before connecting anything to a PC, make sure the drive itself works.

All you need is the drive, its power supply, and a disk you don’t care about too much. Power it on, insert the disk, lock it in place and watch the LEDs. If the drive spins up, reads briefly, and stops without drama, you’re probably fine.

Grinding, repeated resets, or constant head banging (inside the drive, not you) are warning signs.

Getting a C64 disk onto a modern PC

To connect a Commodore disk drive to your PC, you’ll need a serial-to-USB adapter based on the XUM1541 standard (often sold as ZoomFloppy). These aren’t made in huge numbers, so eBay is usually your best bet. Buy carefully and don’t overpay.

(These devices work on Windows and Linux — screenshots are from Ubuntu Linux.)

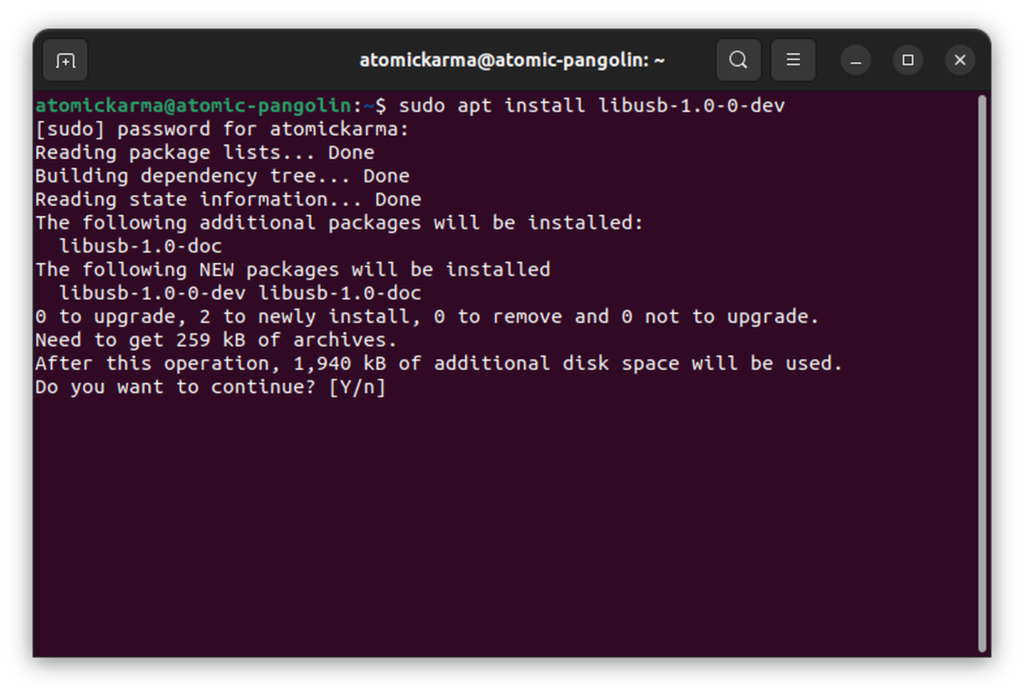

Once connected, the tool you need is OpenCBM — a long-standing set of utilities designed specifically for Commodore drives.

Installation varies by distro, but OpenCBM packages are still available for most mainstream Linux systems. Once installed, you’ll also need libusb, as the XUM1541 interface relies on it.

At that point, you can connect the PC, adapter, disk drive and power supply together.

Creating a disk image

With the drive powered on, OpenCBM lets you confirm it’s responding correctly:

cbmctrl reset

cbmctrl status 8

A working 1541 will report itself immediately.

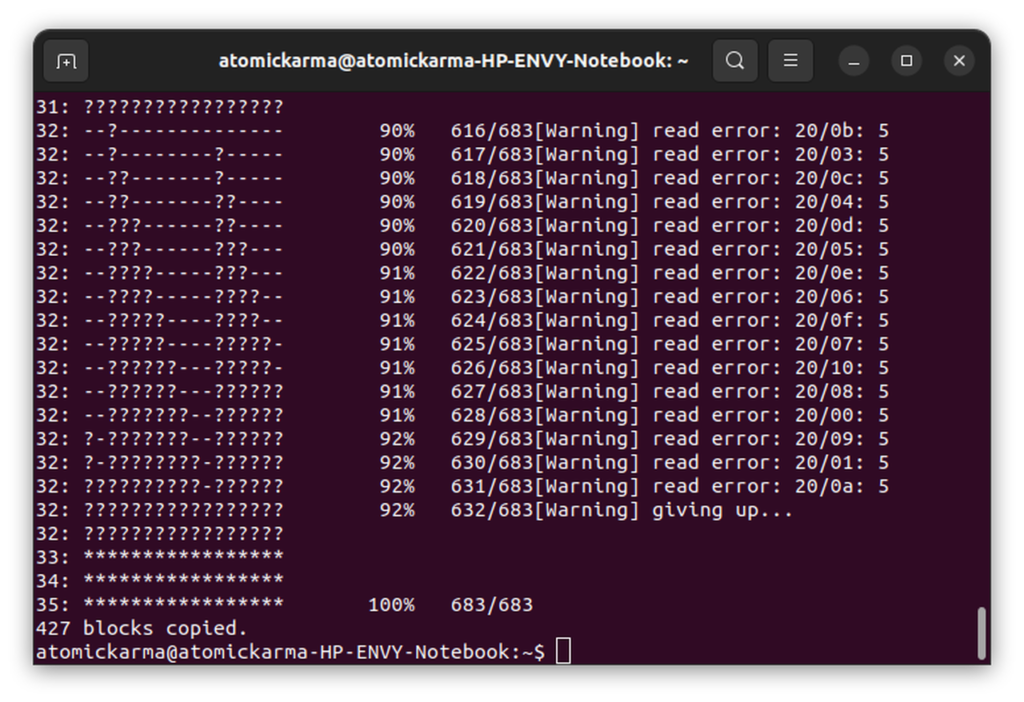

To archive a disk, OpenCBM’s d64copy tool does most of the heavy lifting:

But that’s a whole other rabbit hole.

That’s it. The contents of the physical disk are copied into a single .d64 file. Because C64 disks are tiny by modern standards, the process is usually quick — swapping disks takes longer than imaging them.

If a disk is unreliable, OpenCBM includes options to slow transfers, retry bad sectors, or limit reading to specific tracks. Disks created with fastloaders can be trickier, and sometimes require alternative tools like cbmcopy or imgcopy.

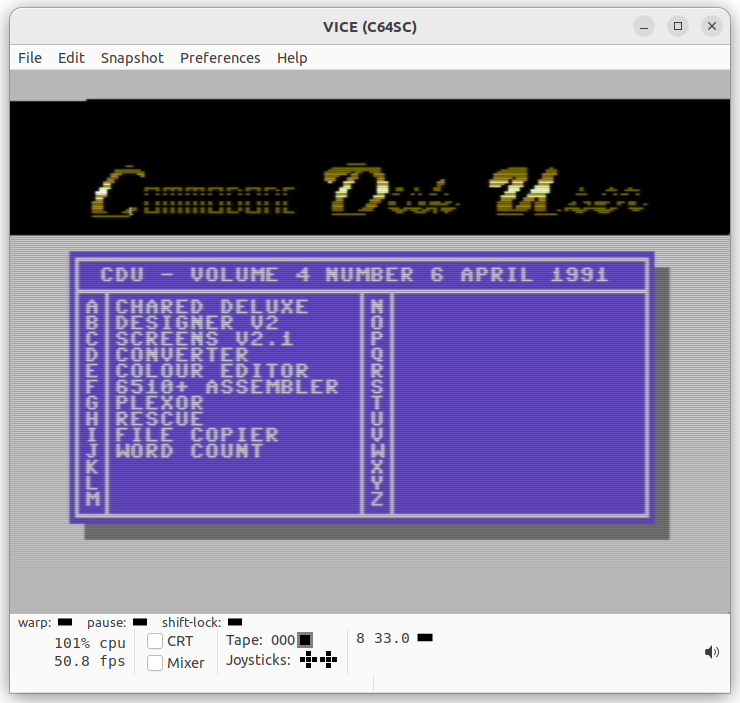

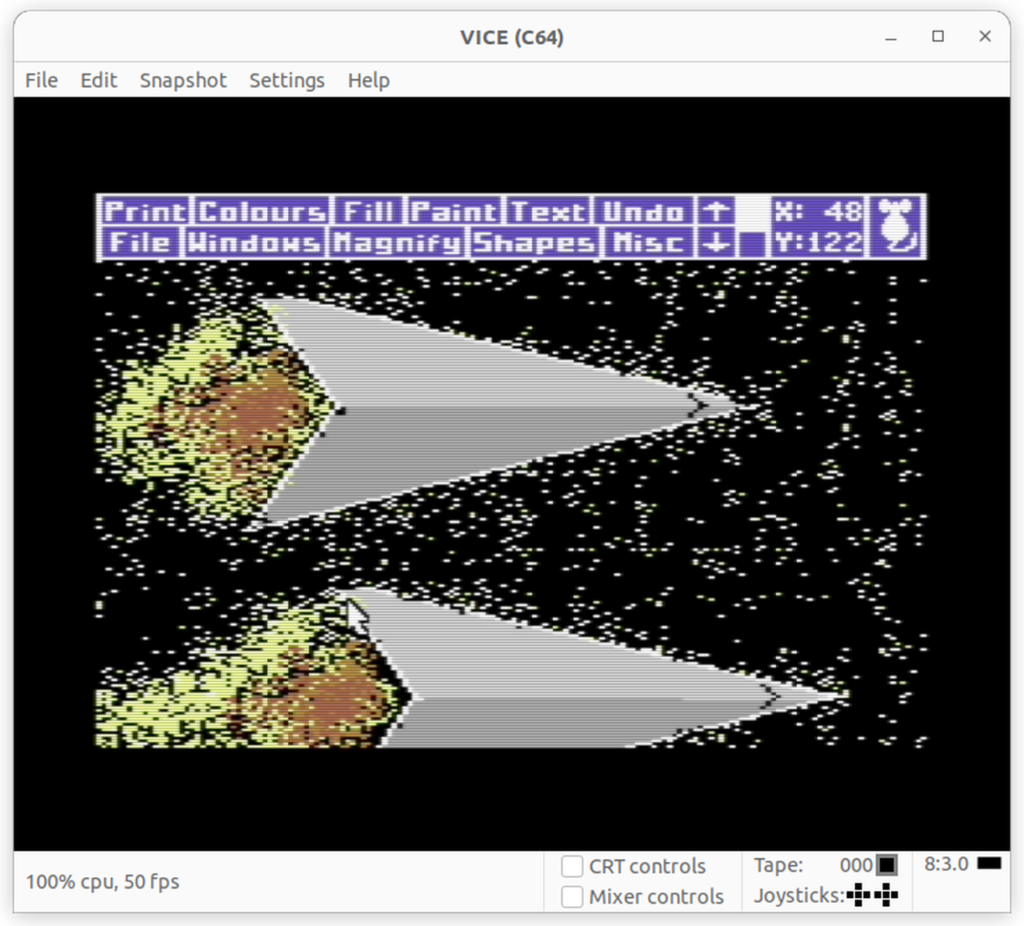

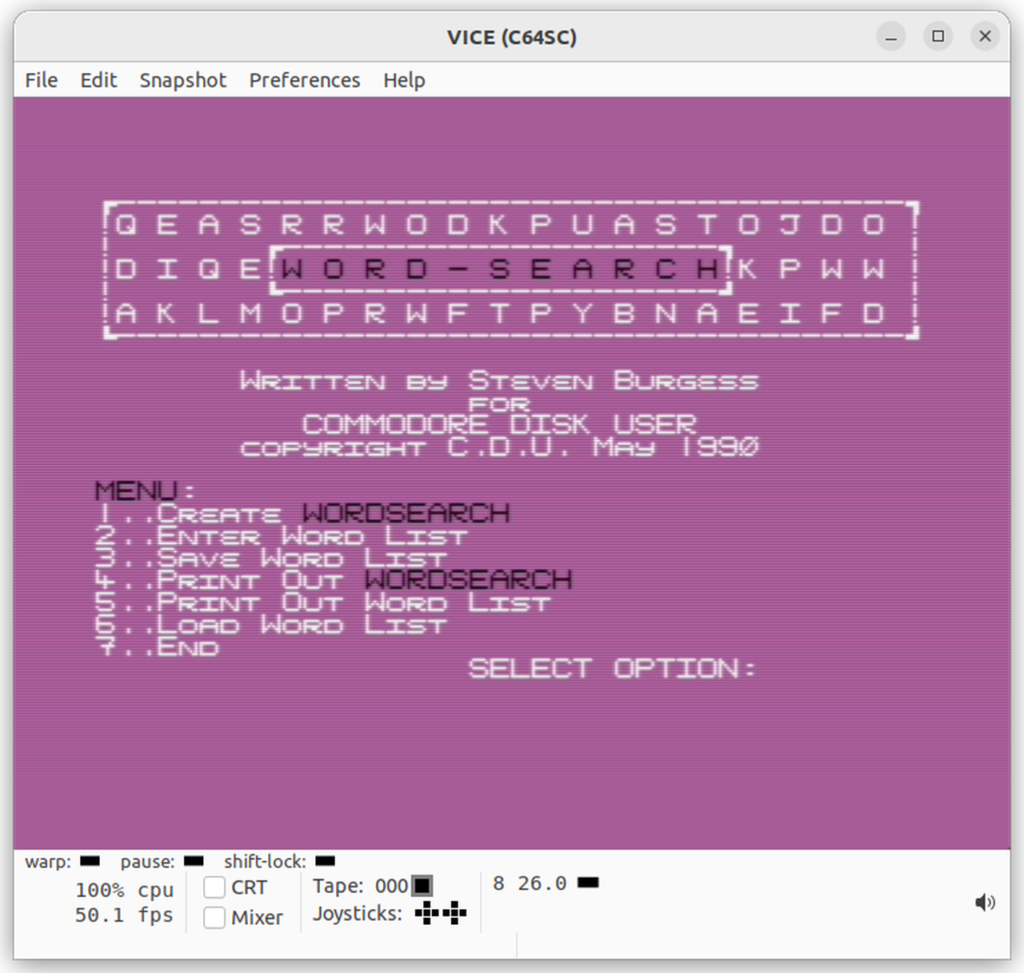

Checking your images with VICE

Once you’ve created disk images, VICE is the easiest way to explore them. You can attach a .d64 file as drive 8, browse its contents, and load software exactly as you would on a real C64.

If an image loads and behaves as expected in VICE, you’ve probably archived it successfully.

Be patient, though. Even on modern hardware, C64 software loads at near C64 speeds in an emulator, unless you enable warp mode.

Keeping things organised

Once you start imaging disks, organisation matters.

Labels fade, handwriting becomes ambiguous, and filenames alone don’t tell the full story. I keep a simple spreadsheet listing disk names, contents, and notes about compression or fastloaders. Photos of the original disks also help.

The idea here is to make sure future-you knows what’s actually on each image.

What comes next?

You might rediscover old artwork, sprites, music, or unfinished projects worth revisiting. You might copy assets to a C64 Mini, share PD material online, or simply archive everything and move on.

Either way, you’ve preserved something very personal and saved it from disappearing altogether.

And once you’ve done disks, well… there’s always cassette tapes. Or you could grab a Commodore 64 Ultimate and connect your Commodore 1541 drive to that and start rescuing your disks that way.

Affiliate Disclosure: Some of the links in this post may be affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through those links. This comes at no extra cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Christian Cawley is the founder and editor of GamingRetro.co.uk, a website dedicated to classic and retro gaming. With over 20 years of experience writing for technology and gaming publications, he brings considerable expertise and a lifelong passion for interactive entertainment, particularly games from the 8-bit and 16-bit eras.

Christian has written for leading outlets including TechRadar, Computer Weekly, Linux Format, and MakeUseOf, where he also served as Deputy Editor.

When he’s not exploring vintage consoles or retro PCs, Christian enjoys building with LEGO, playing cigar box guitar, and experimenting in the kitchen.